Mio padre è nato a Tarantasca in provincia di Cuneo, ai piedi del Monviso – come voleva ricordare- il 23 maggio 1934.

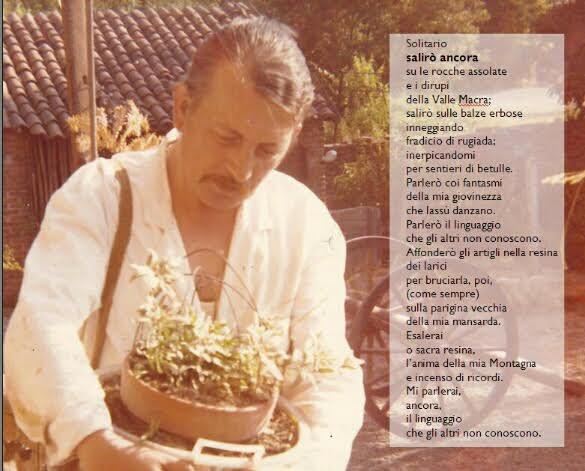

Appassionato fin da bambino di disegno, è approdato alla pittura dai misteriosi confini della musica e della poesia. Era autodidatta; l’arte per la pittura era insita in lui ed egli ha saputo attingervi con grande passione e innata capacità.

All’età di dodici anni ha frequentato il Ginnasio presso l’Istituto Salesiano di Cuneo e, successivamente il Liceo Classico della medesima città dove, per pagarsi la retta puliva i pavimenti e svolgeva mansione di cameriere ai tavoli della mensa, dedicando allo studio le ore notturne.

Nel 1959, grazie ad una borsa di studio, ha compiuto un lungo viaggio in Terra Santa dove ha imparato la lingua araba. Nei tre anni successivi ha vissuto a Cuneo, presso l’Istituto Amedeo Rossi, dove dava ripetizioni private. Successivamente si è trasferito a Mirabello (AL) presso l’Istituto San Giuseppe e, poco dopo, vincendo il concorso di Guardia Campestre, si stabilì a Castellazzo Bormida, dove morì all’età di sessantadue anni, il 28 novembre del 1996, quando io ne avevo 29.

Mio padre non amava gli squallidi elenchi formali che ogni curriculum deve riportare. Egli ha amato sempre le cose piccole e semplici, ignorate dai molti.

Ha amato gli umili, gli indifesi e gli emarginati, in paese era chiamato “ l ’ avvocato dei poveri ”. Ha amato gli animali e la montagna senza mai dipingerli (nella sua pittura sono rarissime le figure di animali e i paesaggi sono spogli). Ha nutrito una grande passione per i libri che, fin da piccolo, con la sua inseparabile bicicletta, andava a comprare sulle bancarelle dei mercati di Torino e Cuneo e che ora, insieme ad importanti tomi, compongono la prestigiosa e fornitissima biblioteca di famiglia.

Ricordo mio padre curvo sui libri, davanti al cavalletto o a catalogare reperti di ogni genere, frutto di una precedente raccolta, oppure me lo ricordo in divisa da Vigile Urbano sempre con la sua bicicletta sia in estate che in inverno ( era l’unico Vigile del paese senza patente); ma di lui ho anche un ricordo doloroso se penso alla vita difficile a causa dei problemi di salute che oggi sarebbero facilmente diagnosticabili: le crisi di ipoglicemia, mai riconosciute, gli causavano forti tremori e, a volte, perdite di conoscenza.

Quando ero piccola mi portava sempre con sé in esplorazione alla ricerca di muschi, licheni, minerali e anche di argilla con la quale spesso mescolava i colori. Oppure mi agghindava con mantella, sciarpa o un cappello e mi ritraeva nell’atto da compiere qualche faccenda (conservo un bel carboncino in cui sto dipingendo al suo cavalletto). Così pure soleva fare con mio nonno materno: gli faceva indossare un giaccone informe, gli metteva in mano un bicchiere di vino (che mio nonno solitamente beveva), eseguiva due schizzi velocissimi e in pochi attimi riusciva a cogliere l’essenza del tutto, lo spirito era immortalato per sempre.

Mio padre era affascinato dalle scene di vita rurale e quotidiana, dai cortili, dai panni stesi, dalle osterie e dai vecchi nodosi che le visitavano…. Aveva sempre con sé un taccuino su cui annotava pensieri e ritraeva persone o scorci del paese. Nei suoi dipinti spesso le sedie hanno due gambe (e i tavoli due o, al massimo, tre), gli uomini sono sempre anziani e le donne quasi sempre giovani. Egli ha sempre modificato i colori commerciali aggiungendo aniline o polvere di ossa di animali o altri misteriosi ingredienti. Nei suoi quadri il rosso non è mai rosso, il blu non è mai solo blu e il verde non esiste. Non ha mai dipinto paesaggi o piante, nonostante la sua grande passione per la natura e la botanica (gli alberi sono spesso spogli o addirittura secchi). I suoi colori sono le ocre e le terre; la luce esplode dai suoi dipinti inondando l’osservatore con rara potenza evocativa, i chiaro-scuri dei suoi interni permeano l’atmosfera antica di ciò che fu. Vasta fu la sua ricerca sperimentale al fine di ottenere nuove tecniche di pittura su tela e cartoncino (ricordo la tecnica “huile chauffer” che consisteva in una tecnica con olio riscaldato).

Me lo ricordo silenzioso e schivo ma anche brillante e dotato di grande ironia. Serio e introverso, appena terminato il servizio, si rinchiudeva nel suo studio dove, pensoso, se ne stava a dipingere, studiare, scrivere… Lungi da me affermare che fosse privo di difetti, nei quali rispecchiava esattamente i molteplici aspetti degli artisti, un po’ disordinato, malinconico, distratto…

Chi entrava nel suo studio, odoroso di resina bruciacchiata, aveva l’impressione di trovarsi in un altro mondo, circondato da tele, cavalletti, colori, brogliacci, minerali, tomi e dagli oggetti più disparati al punto di pensare di essere nell’antro di un naturalista di altri tempi.

Mio padre non era un amante delle opere mastodontiche, i suoi quadri erano sempre a misura di persona, proprio come era lui; egli era la solidale concezione dell’essere che lo faceva padrone di quell’esaltazione figurativa non più riscontrabile ai giorni nostri. Nel corso della sua vita artistica ha ottenuto numerosi riconoscimenti sia in campo figurativo quanto in campo letterario. Ricordo quando, con mia mamma andò venti giorni a Marsiglia per una mostra personale invitato dall’Unesco.

Come la maggior parte dei veri artisti non ha mai saputo trarre profitto economico dalle sue opere, nonostante le eccellenti recensioni e le numerosissime mostre a cui partecipò con grande successo. Il fatto che le sue opere piacessero già bastava a lui per sentirsi gratificato.

Uomo intelligente e modesto, di profonda fede cristiana, di eccezionale genialità, spesso incompreso, è stato pittore, poeta, musicista (nella veste di compositore di brani per pianoforte), scrittore, naturalista, etologo, botanico, inventore, scalatore…

Uomo e padre unico e irripetibile, con la sua vastissima cultura umanistica e artistica ha vissuto tutta la vita pervaso da una insaziabile fame di conoscenza.

Mi ha sempre detto, fin da quando ero bambina, “Io non morirò mai”… ed io gli credo.

Maria Elisabetta